Probate FAQs

General Probate

Probate is the legal procedure in which an estate is settled, debts are paid, and assets are distributed to beneficiaries or heirs. Click on each of the FAQs to learn more.

General Probate FAQs

What is Probate?

Probate is the legal process used to settle an estate, pay off debts, and assign assets to heirs or beneficiaries. To initiate the probate process—which is managed by the state's probate court—one must first establish the validity of any will, if any, and then name an executor to manage the estate until a settlement is reached.

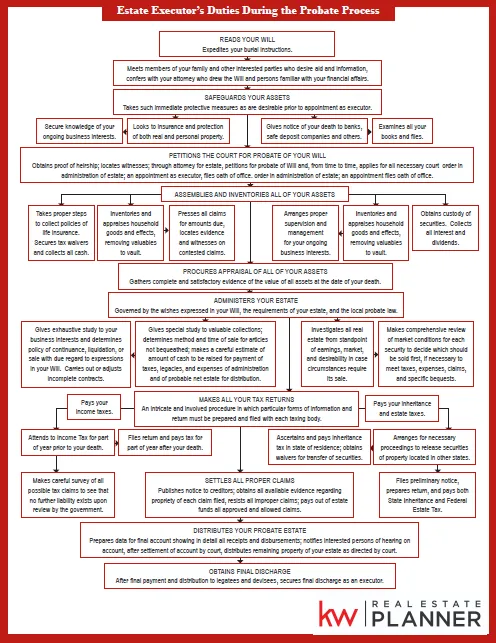

How does the probate process work?

States have different processes for probate. Certain states also offer a streamlined probate procedure for modest or straightforward estates. As a general rule, however, probate typically entails a number of procedures meant to authenticate the will, guarantee that its directions are followed (should one exist), settle estate debts, and allocate any remaining assets to the heirs and designated beneficiaries.

Typically, probate goes through the following procedures:

If there is a will, it is submitted to the probate court.

A notice of Petition for Probate is published and a personal representative is appointed. After that, the executor or administrator formally requests that the court probate the decedent's estate.

For a certain amount of time, creditors may file claims against the estate.

The personal representative locates and collects the estate's possessions. These resources need to be preserved and protected.

When required, assets are liquidated to pay valid claims against the estate.

The personal representative files a final tax return.

A final petition is filed with the court to explain expenses, assets received and disbursed, how funds were used, and which debts were paid.

Once the petition is approved, assets are distributed to beneficiaries and heirs and the estate is settled.

Probate procedures alter slightly when a person passes away without a will. The court will appoint an administrator in this instance. The administrator finds and values assets and debts, distributes assets, and identifies heirs in the same manner as a personal representative or executor. The administrator of adult children is typically a spouse or domestic partner in most states. The intestate succession rules of the state will govern the distribution of the estate's assets.

How long does probate usually take to complete?

As a general rule, the probate process takes 6 to 18 months, but it can extend beyond that for more complex cases. It's essential to note that these are general estimates, and the actual duration can vary based on the specific circumstances of the estate and any unforeseen complications that may arise. On some occasions, probate can even take 1-3 years or even longer. There are many factors that can affect the probate process.

If any of these complications arise, the probate process could take several years.

The state’s probate court process.

Difficulty finding beneficiaries or heirs.

The number of beneficiaries and their residences.

A contest of the will by beneficiaries or heirs.

Real estate and property that are difficult to sell.

Liens and claims against the estate that are unsettled liens.

Failing to notify creditors during the claim period.

A personal representative who neglects their legal obligations.

The estate is large enough to owe estate taxes.

How is the probate process started?

When someone dies, probate doesn't start right away. Upon identification of a will, the designated executor may initiate the probate procedure by submitting a petition to the court seeking formal recognition as the executor. It is also necessary to file the death certificate and will.

In the event that no will is present, an administrative procedure is initiated. To choose an administrator for the estate, a petition still needs to be submitted to the probate court.

Following the filing of this petition, the court sets a hearing date to either approve the executive or administrator or hear any objections. All beneficiaries and heirs of the deceased must be notified of the hearing. After an executive or administrator is accepted, the court opens a probate case and the individual has the legal power to act on behalf of the estate.

Why is probate required?

Probate may appear to be nothing more than an expensive and time-consuming process, yet it serves numerous vital purposes. Probate is used to safeguard an estate's assets, make sure the correct beneficiaries or heirs receive them, and make sure debts and taxes are paid. Another purpose of probate is to ensure that a will is legitimate and the true wishes of the deceased are carried out.

The following are the main goals of probate and the reasons it's necessary:

Gives recipients and heirs a formal title transfer or ownership of assets and property. This guarantees that recipients will obtain a clean title and that the property cannot be mortgaged or otherwise disposed of.

Ensures that any taxes due, including those arising from the transfer of estate property, are paid by the decedent and/or the estate.

Provides a way for creditors to get their debts settled. Creditors have a deadline to submit claims during probate. This guarantees that debts are settled before assets are allocated to recipients and heirs, shielding them from future claims.

Protects assets to ensure that beneficiaries and heirs receive them. Otherwise, property could be easily stolen or sold.

Ensures that assets and property are allocated following the decedent's wishes to the appropriate individuals or groups.

Keep in mind that not all assets must go through probate, and not all estates require probate. By using alternative ownership and title options, such as immediately transferring property and assets to heirs and beneficiaries without going through the court system, this legal process can be circumvented in many ways.

How much does probate cost?

The cost of probate depends on many factors including:

State law

Local practices

Complexity of the estate

Whether a probate attorney is involved

Whether the will is challenged

Executor fees, if any

The cost of the surety bond

Probate fees typically range from 2% to 7% of the estate's total worth. Complex estates may incur considerably more costs, particularly if there is a will contest. Numerous predetermined costs are not negotiable or adjustable. Your state can have a big impact on costs. With many professionals you will use, you may be able to negotiate a lower rate, however, even when the statute provides for a percentage fee.

If the estate is very small, is probate still required?

Many estates don't need probate, however it varies depending on the kind of property and the estate's value. Probate is not required if the estate's assets are intended to transfer to recipients outside of it

To determine whether the estate qualifies for a simplified probate process or if there have been any changes to the rules, it is recommended to consult with a probate expert or check with the Washington State courts for the most up-to-date information. Legal professionals can provide guidance based on the specific details of the estate and ensure compliance with current state laws and procedures.

What happens during probate of an uncontested will?

When a will is not contested, the process described above for probate applies. A hearing on the petition will be held following the will's admission to the court to allow prospective beneficiaries and heirs to raise objections. The court designates the personal representative in the event that no objections are raised. Until the estate is finalized, a contest may still be brought, depending on the state.

Where is probate handled?

Probate is handled by the probate court in the county and state in which the decedent lived as their primary residence at the time of death. Note that this refers to the decedent’s state of primary residence, not where they may have been living or vacationing when they passed away.

Do I need a probate lawyer?

There is almost never a legal requirement to use a lawyer during the probate process, although probate can be complex and very formal. A missed deadline or failing to follow proper procedures can result in an executor being liable for mistakes or debts, for example. As a general rule, a probate lawyer is advisable for estates that are large or complex enough to require probate.